Bright, Susie and Rachel Kramer Bussel, eds. | Best Sex Writing 2012 (Cleis Press, 2012). Susie Bright frames this year's anthology in the following way: "On one side of the current sex news we have the orgasm guru, the pleasure benefactor, the inspirational bohemian ... the writers of these pieces describe an erotic identity unfettered by shame, a marvel in all its variety, the authentic glue that keeps us going, both literally and philosophically ... [on the other side] fearmongers of our 21st-century Gilded Age are fanatical about social control through sex, largely using women and young children as bait" (viii). So, you know, she obviously has a perspective! But it's Susie Bright, so what did you expect, and for the most part I'm on board with that perspective, so I'm willing to hop on for the ride. It was a good collection, but in a lot of ways made me sad about how unable we are as a culture to talk about and appreciate human sexuality. You can check out the anthology's full table of contents, read Rachel Kramer Bussel's introduction, and watch a web video book trailer over at the book website.

Bright, Susie and Rachel Kramer Bussel, eds. | Best Sex Writing 2012 (Cleis Press, 2012). Susie Bright frames this year's anthology in the following way: "On one side of the current sex news we have the orgasm guru, the pleasure benefactor, the inspirational bohemian ... the writers of these pieces describe an erotic identity unfettered by shame, a marvel in all its variety, the authentic glue that keeps us going, both literally and philosophically ... [on the other side] fearmongers of our 21st-century Gilded Age are fanatical about social control through sex, largely using women and young children as bait" (viii). So, you know, she obviously has a perspective! But it's Susie Bright, so what did you expect, and for the most part I'm on board with that perspective, so I'm willing to hop on for the ride. It was a good collection, but in a lot of ways made me sad about how unable we are as a culture to talk about and appreciate human sexuality. You can check out the anthology's full table of contents, read Rachel Kramer Bussel's introduction, and watch a web video book trailer over at the book website.Clarke, Ted | Brookline, Allston-Brighton, and the Renewal of Boston (The History Press, 2010). Growing up and living in the same town for twenty-seven years, I took for granted knowing the basic contours of local history. I've lived here in Boston since 2007 -- working at the Massachusetts Historical Society no less! -- and what with one thing and another still know relatively little about the history of the Boston metropolitan area. But I've been working on a research project recently that's actually pushed me to delve a bit more into local history. More on that eventually, when I've got the paper written, but in the meantime it was fun to spend an afternoon reading Ted Clarke's brief overview of Boston and its relationship to Brookline and Allston-Brighton, both of which I spend a lot of time in. Lack of footnotes and a bibliography make me take Clarke's historical narrative with a grain of salt, but reading his book has prompted me to consider more deeply the history of the area I now call home.

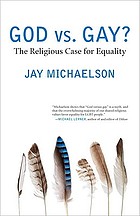

Michaelson, Jay | God vs. Gay?: The Religious Case for Equality (Beacon Press, 2011). Part of the Queer Action/Queer Ideas series edited by Michael Bronski, Michaelson's God vs. Gay, as the subtitle suggests, makes a "religious case" for recognizing queer sexuality as part of the variety of God's creation. An observant Jew with a background in New Testament scholarship, Michaelson admits up-front that he'll focus on Judeo-Christian tradition. What I like best about this slim volume is its emphasis not so much on how homophobic interpretations of scripture are incorrect and ahistorical (though he covers that), but about the religious injunctions toward lovingkindness for humanity. "Loneliness is the first problem of creation," Michaelson writes, "and love comes to solve it" (6). While this book is not likely to convince the Biblical literalist, it may give sex-positive religious folks some new, and possibly more effective, language to talk about why human sex, gender, and sexual diversity can be part of religious life rather than a departure from it.

Young-Bruehl, Elisabeth | Childism: Confronting Prejudice Against Children (Yale U.P., 2012). I picked up psychoanalyst Young-Bruehl's book hoping for a good systemic analysis of the social marginalization (and simultaneous idealization/objectification) of young people in our culture. Indeed, Young-Bruehl's goal in writing the book was to introduce the term "childism" as something equivalent to "sexism" or "racism" that would help us identify the patterns of age-based prejudice and stereotyping which lead to age-segregation, intolerance, and inequality. Frustratingly, this is not that book. As a therapist and theorist whose work focused primarily on children who were subject to physical and emotional abuse, Young-Bruehl's narrative actually works against her desire to convince her audience that age-based prejudice against young people is a thing in the world. Her examples are so obvious and horrific (children who were sexually abused by family members, gross neglect, etc.) that readers not already thinking in terms of inequality will say, "Yes, of course that's wrong! Children should be protected!" but likely fail to examine their own every-day prejudices about children's ability to participate in society. In addition, her rhetoric and examples are, for obvious reasons, wrapped up in psychoanalytic language and often in response to very specific developments within the professional fields in which she practiced. Hopefully, this book will speak to her fellow practitioners and shift the debate in healthy directions. However, to the non-specialized reader she comes off out of touch with the parents and activists who have been speaking out regularly on this issue consistently in online spaces and through real-world actions (like protests against the freak-outs over breastfeeding in public). For an introduction to the concept of age-based prejudice, I'd recommend Helping Teens Stop Violence, Build Community, and Stand For Justice.

Younge, Gary | Who Are We -- and Should It Matter in the Twenty-First Century? (Nation Books, 2011). English-born journalist Gary Younge explores the good, the bad, and the ugly of our identities, politicized and otherwise. I admit that I was a bit wary, given the title of this book, that Younge's thesis would be reduced to a call for the end to "identity politics" -- but Who Are We is much more than that. Even though the text wanders at times, I found his thoughtful treatment of the many ways in which we invoke our many-layered identities (and society invokes them for us, sometimes contrary to our own self-understanding) to be extremely nuanced and articulate. Growing up black and working-class in England during the 1970s, Younge has a clear understanding of how inequality shapes self-awareness: "Those who feel without identity [the powerful] do not see the need to meet people halfway and thereby fail to recognize that everyone else is doing all the traveling" (45). He eloquently treats such thorny subjects as the present-day use of the term "political correctness," questions of intersectionality (how pitting "African-American" against "woman" in the oppression olympics ignores the existence of people who are both), and the importance of honoring self-definition: "We should honor self-definition not to humor the subject but because it is infinitely preferable to allowing anyone to be defined by others" (84). I'd highly recommend this book for anyone interested in how our self-identities and community affiliations become politicized -- and how those politics can both support and detract from the quest for equality.

Nestle, Joan | A Fragile Union: New and Selected Writings (Cleis Press, 1998). A Fragile Union brings together a series of fiction and non-fiction pieces by lesbian activist Joan Nestle, one of the founders of the Lesbian Herstory Archives (one of the largest community-based archives chronicling queer women's history in the world \o/). Published over a decade ago, when Nestle was with colon cancer, this work stands as a fractured memoir, bringing together pieces reflecting back into her mid-twentieth-century adolescence, the early years of gay liberation, and feminist activism, and forward into the future of queer identities and practices. Given my reading list over the past few months, I particularly appreciated the moments at which Nestle's experiences overlap and converse with the work of others in her cohort, such as Gayle Rubin and Pat Califia. And for obvious reasons, I hold a special place in my heart for the anyone who has done as much as Nestle to ensure the survival of primary source materials on queer women's lives for future generations to plunder for story-telling, history-making potential.

Cross-posted at The Pursuit of Harpyness.