As we reach the end of July it's time for another catch-all post of mini-reviews for books I've read but haven't had time to substantively review. CrowGirl and I are busy with life in the upcoming months of August and September (among other things getting married and going on our honeymoon) so anticipate light posting around here until October.

Virgins: A Novel | Caryl Rivers (St. Martin's 1984; 2012). Rivers' novel about Catholic High School seniors coming-of-age in the 1970s is being re-issued this fall as an e-book; I received an advance review copy and read it on a sweltering afternoon earlier this month. It was a quick and satisfying beach (or in this case bathtub) read, and reminded me of nothing so much as the film Saved! -- though obviously with a different set of historio-cultural references. The characters are Catholic, not Protestant Evangelical, and no one gets knocked up by their gay friend while trying to turn him straight. Instead we have the earnest Catholic-college-bound Peggy, her boyfriend Sean (bound for the priesthood), and Peggy's looking-for-trouble Constance Marie ("Con"). Since I've started writing smut I'm more intentionally interested in how sex scenes play out in novels -- and I will say (mild spoilers!) I was pleasantly surprised by the positive and tender nature of what we're calling these days "sexual debut"; both Sean and Peggy are enthusiastic participants and neither appear to regret their decision -- nor attempt to bookend it with marriage. It's always heartening to see teen sex (or, you know, any sex really) portrayed in positive yet realistic ways.

The Accidental Feminist: How Elizabeth Taylor Raised Our Consciousnesses and We Were Too Distracted by Her Beauty to Notice | M.G. Lord (Walker & Co., 2012). I picked up a $1 advance review copy of Lord's brief biography of Taylor at Brattle Book Shop after hearing an author interview on the RhRealityCheck podcast. I was particularly intrigued, listening to the interview, by Lord's description of the Production Code Administration and how Taylor's films were often a process of push-and-pull with the authorities over themes of gender non-conformity, defiance of religion, homosexuality, abortion, etc. Unfortunately, The Accidental Feminist spends less time on the evidence of censorship, revision, and defiance that can be mined in the archives and the films themselves -- and more trying to convince us, on precious little evidence, that Taylor herself was a driving force in ensuring "feminist" readings of the characters she portrayed on screen. While a fresh examination of Taylor's career may be in order, I felt throughout that Lord was over-egging the cake and that her case could have been strengthened -- or at least clarified -- by more attention to the historical context. Particularly surrounding feminism, in which Taylor came of age and rose to stardom. For example, in Lord's reading of Giant (1956) she argues that Taylor's character -- the East Coast bride of a Texas rancher -- is somehow more feminist than the rancher's gender-nonconforming spinster sister, in part because Taylor's Leslie is more feminine. Troubling on multiple levels, this analysis ignores the way in which butch single women in cinema during this period were often coded dangerously lesbian, sociopathic, and feminist. To champion Taylor's character in part because of her gender conformity seems distinctly ahistoric as well as not very feminist, at least to my way of thinking! All in all, not recommended if you're looking for a cultural history analysis of the role Taylor and her filmography played in gender debates of the 20th century.

The Gay Metropolis: 1940-1996 | Charles Kaiser (Houghton Mifflin, 1997). For some reason, this past month, I found myself reading two of the standard histories of queer life and activism in America -- the first being Kaiser's history of gay New York from WWII through the early days of the AIDS epidemic. Like Marcus' Making Gay History (see below), Gay Metropolis draws heavily on personal reminiscences. I particularly enjoyed the stories told by interviewees who had come of age before gay liberation or organized activism -- men and a few women who recalled falling in love and having same-sex relationships in times and places were those experiences had little political resonance. Though obviously political ramifications if the individuals were caught, arrested, fired, blacklisted, or otherwise discriminated against. Despite the subtitle's claim that this is a history of "gay life in America," it focuses heavily on urban areas and largely on a gay male population that moves through various metropolitan areas on the east coast -- most notably New York City. Taken for what it is, however, this is a highly readable narrative with a number of valuable first person accounts of the social, cultural, and political experiences of gay and lesbian folks in 20th century urban America.

Making Gay History: The Half-Century Fight for Lesbian and Gay Equal Rights | Eric Marcus (2nd ed.; Perennial, 2002). Originally published in 1992 under the title Making History, this ambitious oral history of gay and lesbian activism since the 1950s draws on over sixty interviews with prominent figures in the movement to tell an on-the-ground narrative of the fight for equal rights from the Mattachine Society to Lambda Legal and ACT UP. These oral histories are heavily edited into gobbets of personal reminiscence interspersed with contextual notes by Marcus. As with any "pure" oral historical narrative, I found myself wishing at times for more analysis. However, these oral histories will be invaluable sources for historians in years to come -- and I devoutly hope that Marcus has taken steps to ensure the unedited versions are secured in a repository somewhere to be accessed and utilized by researchers in perpetuity. His interviewees are both well-known names (Larry Kramer, Randy Shilts, Ann Northrup, Barbara Gittings) and lesser-known individuals whose actions have nonetheless had a profound effect on our understanding of the queer experience and often had a major influence in the political arena. For example Steven Cozza, a teenage Boy Scout who campaigned for the Boy Scouts of America to rescind their policy of excluding non-straight members, or Megan Smith, one of the techies behind PlanetOut -- an early Internet space for queer socializing and activism. I'm glad to have added this volume to my reference library.

(As a side-note, this book is responsible for the only literature-based pick-up I've ever experienced, when a waitress at the restaurant where I was waiting for Hanna saw me reading it and suggested I might enjoy Provincetown's "Girl Splash 2012"; after all the porn I've read on the subway THIS is what inspires the overtures? And they say history isn't sexy.)

Breeders: Real-Life Stories from the New Generation of Mothers | Ariel Gore and Bee Lavender, eds. (Seal Press, 2001). I was pleasantly surprised by this anthology of essays by mothers about their journey to and through pregnancy and parenting. It contains a diverse mix of voices --a range of ethnicity and class, geographic locations, family shapes, and parenting styles. We get Allison Crews' meditation on teenage motherhood and her decision not to surrender her son for adoption ("When I Was Garbage"), Sarah Manns essay on the path she and her wife took toward adoption ("Real Moms"), and Ayun Halliday's heartbreaking "NeoNatal SweetPotato," scenes from the stay she and her daughter faced postpartum in neonatal intensive care. Stories of parenting in violence-ridden urban slums and yuppie enclaves, stories of parenting on the road and in the backwoods with no plumbing and (gasp!) no email. Stories of upper-middle-class striving and stories of precarious food-stamp subsistence. Every reader will find a few pieces irritation inducing, a few pieces deeply moving. Parenting -- and family life more generally -- is particular: We all make decisions based on resources and circumstance and what we believe is best for both ourselves and families. Because family formation is in the cultural spotlight right now thanks to wrangles over marriage equality, divorce, abortion, evolving gender roles, assisted reproductive technology regulation, etc., our personal decisions are interrogated and judged -- and usually found wanting by someone, somewhere. And in turn, we find ourselves judging the decisions of others. I'd say the strength of Breeders is that it gives us a series of windows into the myriad ways in which pregnancy, birth, and parenting intersected with the lives of women at the turn of the millennium.

Showing posts with label feminism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label feminism. Show all posts

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

booknotes: america and the pill

Footnote-mining Bodies of Knowledge and The Morning After brought me to Elaine Tyler May's America and the Pill: A History of Promise, Peril, and Liberation (Basic Books, 2010). May is an historian of mid-twentieth century America family life whose previous work includes a history of childlessness in "the promised land" and the family in Cold War America. Her parents were also, incidentally, involved in the development and early clinical trials of the birth control pill, so her personal history is also intertwined with the story she seeks to tell about Americans and the introduction of hormonal contraceptive pills from the 1950s to the present.

America and the Pill is a highly readable, solidly-researched history of the development, distribution, and use of the birth control pill in America since the fifties. In seven brief chapters (I read the book in an afternoon) May describes the development and testing of the pill, its promotion by politicians and thought leaders interested in population-control, its use by married couples, the pill's role in the sexual revolution, the search for hormonal contraceptives for men, "questioning authority," and public use and perception of the pill today.

Clearly written as an introductory overview, this history begs for further elaboration on a number of points -- for example, the complicated relationship between individual use of birth control and national and international attempts to limit population growth. I would also be interested in a further exploration of how perceptions and use of the pill as a method of birth control relates to concerns about the spread of sexually-transmitted infections. For example, can we see a significant shift in what populations use the pill vs. the condom before and after the advent of AIDS/HIV?

I would also like to see further elaboration on the discourse concerning libido and hormonal birth control, since concerns over low libido remain a primary barrier to developing a male birth control pill, while women's persistent reporting of side-effects of the pill, including lowering of libido, have been glossed over as psychosomatic or unimportant when compared to the goal of limiting population growth. May offers an interesting historical perspective on this issue:

I felt at points that May was deliberately writing for a lay audience (that is, an audience of non-historians, or those unfamiliar with the history of twentieth-century medicine). For example, when she describes the clinical trials of the birth control pills which were undertaken without informed consent on populations such as mental patients and prisoners, she is at pains to point out that such trials were standard operating procedure until well into the 1980s when such violations of bodily autonomy and ethical mismanagement became the subject of public debate and regulation. At times, May's efforts to contextualize the clinical trials spills over into what feels like a bit too much post-facto justification. For example, when writing about the trials conducted in rural Puerto Rico in the mid-50s she writes,

These passing editorial moments aside, May has written a great introduction to the historical context of the birth control pill that will be an enjoyable -- and historically robust -- read for anyone interested in the topic of women's and sexual/reproductive health, history of medicine, history of the family, and related fields.

America and the Pill is a highly readable, solidly-researched history of the development, distribution, and use of the birth control pill in America since the fifties. In seven brief chapters (I read the book in an afternoon) May describes the development and testing of the pill, its promotion by politicians and thought leaders interested in population-control, its use by married couples, the pill's role in the sexual revolution, the search for hormonal contraceptives for men, "questioning authority," and public use and perception of the pill today.

Clearly written as an introductory overview, this history begs for further elaboration on a number of points -- for example, the complicated relationship between individual use of birth control and national and international attempts to limit population growth. I would also be interested in a further exploration of how perceptions and use of the pill as a method of birth control relates to concerns about the spread of sexually-transmitted infections. For example, can we see a significant shift in what populations use the pill vs. the condom before and after the advent of AIDS/HIV?

I would also like to see further elaboration on the discourse concerning libido and hormonal birth control, since concerns over low libido remain a primary barrier to developing a male birth control pill, while women's persistent reporting of side-effects of the pill, including lowering of libido, have been glossed over as psychosomatic or unimportant when compared to the goal of limiting population growth. May offers an interesting historical perspective on this issue:

Although today's pill may not suppress libido more than the original oral contraceptive did, women today may well experience the effect of the pill differently. For many in the first generation of pill users, the intense fear of pregnancy diminished women's libido to such an extent that when they went on the pill and that fear disappeared, their sexual pleasure was increased considerably. Today there is no longer the terror of facing an illegal abortion, a ruined reputation, banishment to a home for unwed mothers, or a hasty marriage. ... With so many contraceptive options available to women today, some are unwilling to compromise their sexual pleasure of the convenience of the pill (149).While women's sexual pleasure is here understood in tension with their desire to manage their fertility, men's sexual pleasure (even their gender identity) is situated in their ability to procreate -- with no corresponding desire to limit family size. May quotes one medical doctor who in 1970 wrote in the Boston Globe that "generally speaking, a man equates his ability to impregnate a woman with masculinity. And all too often the loss of such ability really deflates his ego" (99). Presumably, many individual men in the 60s and 70s desired to take measures to ensure their partners did not get pregnant -- but while medical personnel and the public at large understood the fear of pregnancy and/or the desire to limit or space pregnancies as a legitimate concern for women, it appears they did not assume the same for men.

I felt at points that May was deliberately writing for a lay audience (that is, an audience of non-historians, or those unfamiliar with the history of twentieth-century medicine). For example, when she describes the clinical trials of the birth control pills which were undertaken without informed consent on populations such as mental patients and prisoners, she is at pains to point out that such trials were standard operating procedure until well into the 1980s when such violations of bodily autonomy and ethical mismanagement became the subject of public debate and regulation. At times, May's efforts to contextualize the clinical trials spills over into what feels like a bit too much post-facto justification. For example, when writing about the trials conducted in rural Puerto Rico in the mid-50s she writes,

The developers of the pill were particularly concerned about its safety. They put in place elaborate precautions to monitor the health of the women who took part in the trials, such as frequent medical exams and lab tests. Study participants in impoverished areas received medical attention vastly superior to what was normally available to them. ... By the standards of the day, the studies were scrupulously conducted (31).While all of these statements may be factually accurate (and I have no reason to suspect they are not), these passages feel a little too much as if May is trying to forestall protests about how these trials were conducted, protests which -- while not undermining the data collected -- would certainly be legitimate. What sort of pressure were poverty-stricken Puerto Rican women under to participate in the trials, for example, if the healthcare they received as a result was "vastly superior to what was normally available"? Obviously, it's important to understand these medical protocols in the historical context in which they happened, but it feels a little like May is trying to preempt discussion of ethical implications.

These passing editorial moments aside, May has written a great introduction to the historical context of the birth control pill that will be an enjoyable -- and historically robust -- read for anyone interested in the topic of women's and sexual/reproductive health, history of medicine, history of the family, and related fields.

Tuesday, May 29, 2012

booknotes: joining the resistance

Psychologist Carol Gilligan is something of a controversial figure in feminist circles. Her work on young women's psychological health (In a Different Voice) is widely read and widely criticized for dramatizing adolescent girls' experience in unhelpful, alarmist ways; I once had a Women's Studies professor, herself a psychologist, react to the news I was reading Gilligan's The Birth of Pleasure (Knopf, 2002) with caution, pointing out gently that her theories often seemed to rely on assumptions about gender essentialism that sat uncomfortably with many.

As an instinctive anti-essentialist (at least when it comes to gender) I remember being a bit surprised that Gilligan's arguments would be taken that way -- since that wasn't the sort of psychological landscape I saw her outlining in Pleasure. Weaving together reflections on canonical female truth-tellers (drawing on her background in English literature) and her psychological research, Gilligan is primarily interested in how individuals -- of any gender -- speak or stay silent about what they know. Drawing on theories of developmental psychology, psychoanalysis, a feminist analysis of the kyriarchy, Gilligan argues that human beings are born into the world with a full range of psychological resources which are then curtailed by gender policing which in turn causes psychic trauma.

Drawing parallels between preschool age boys and middle school age girls, Gilligan suggests that at points when growing beings are initiated into new levels of patriarchal control, we see increased instances of acting-out and destructive behavior (toward the self and others). Because girls experience this trauma at a later developmental stage than boys, she argues, women as a population are more likely to be able to articulate what they have lost in the initiation process, and to have the resilience to push back successfully. Men, she theorizes, can often identify the trauma of being forced into male-stereotyped behavior, but because it happened so early in childhood have a very difficult time accessing memories of their humanity before certain ways of being were rendered off-limits due to gendered expectations.*

Which brings us to Gilligan's latest work, a slim volume titled Joining the Resistance (Polity Press, 2011). Half reflection on her body of work, half call to action, Resistance shares some of the highlights of Gilligan's research in an accessible way and makes a passionate appeal for re-connecting with the parts of our humanity that the oppositional gender-binary has robbed from us. "Our ability to love and to live with a sense of psychic wholeness hinges on our ability to resist wedding ourselves to the gender binaries of patriarchy," she argues, in language that should make any feminist worth her salt jump for joy (109). This recalls the research Phyllis Burke cites in Gender Shock which suggests that the individuals least invested in maintaining oppositional gender roles are those most adaptive and resilient in the face of hardship and trauma.

Gilligan, following such humanist psychologists and philosophers as Eric Fromm, Abraham Maslow, and Carl Rogers, pushes us to reconsider our assumptions concerning the fundamental nature of humanity. While resisting any simplistic arguments that human nature is "good" (vs. "bad"), she suggests that we might reconsider widespread assumptions about human self-interest and cruelty. We might do well, she suggests, to listen to those who resist inflicting violence and trauma -- and rather than frame them as exceptions to the rule, think of them as survivors of an indoctrination process:

I'll leave you with one of my favorite passages from the book, which I posted on Tumblr last week with the comment that, while "secure relationships" are obviously not limited to parent-child connections, this is a strong argument that if we want to strengthen marriage and families, we ought to be legalizing (and advocating for!) poly relationships:

*At the very end of Resistance, Gilligan brings in recent research on adolescent boys, which suggests that they, like the adolescent girls whom Gilligan has spent her professional life studying, experience the dissonance and limitations of patriarchy. I'd love to see her (and others) develop this further.

As an instinctive anti-essentialist (at least when it comes to gender) I remember being a bit surprised that Gilligan's arguments would be taken that way -- since that wasn't the sort of psychological landscape I saw her outlining in Pleasure. Weaving together reflections on canonical female truth-tellers (drawing on her background in English literature) and her psychological research, Gilligan is primarily interested in how individuals -- of any gender -- speak or stay silent about what they know. Drawing on theories of developmental psychology, psychoanalysis, a feminist analysis of the kyriarchy, Gilligan argues that human beings are born into the world with a full range of psychological resources which are then curtailed by gender policing which in turn causes psychic trauma.

Drawing parallels between preschool age boys and middle school age girls, Gilligan suggests that at points when growing beings are initiated into new levels of patriarchal control, we see increased instances of acting-out and destructive behavior (toward the self and others). Because girls experience this trauma at a later developmental stage than boys, she argues, women as a population are more likely to be able to articulate what they have lost in the initiation process, and to have the resilience to push back successfully. Men, she theorizes, can often identify the trauma of being forced into male-stereotyped behavior, but because it happened so early in childhood have a very difficult time accessing memories of their humanity before certain ways of being were rendered off-limits due to gendered expectations.*

Which brings us to Gilligan's latest work, a slim volume titled Joining the Resistance (Polity Press, 2011). Half reflection on her body of work, half call to action, Resistance shares some of the highlights of Gilligan's research in an accessible way and makes a passionate appeal for re-connecting with the parts of our humanity that the oppositional gender-binary has robbed from us. "Our ability to love and to live with a sense of psychic wholeness hinges on our ability to resist wedding ourselves to the gender binaries of patriarchy," she argues, in language that should make any feminist worth her salt jump for joy (109). This recalls the research Phyllis Burke cites in Gender Shock which suggests that the individuals least invested in maintaining oppositional gender roles are those most adaptive and resilient in the face of hardship and trauma.

Gilligan, following such humanist psychologists and philosophers as Eric Fromm, Abraham Maslow, and Carl Rogers, pushes us to reconsider our assumptions concerning the fundamental nature of humanity. While resisting any simplistic arguments that human nature is "good" (vs. "bad"), she suggests that we might reconsider widespread assumptions about human self-interest and cruelty. We might do well, she suggests, to listen to those who resist inflicting violence and trauma -- and rather than frame them as exceptions to the rule, think of them as survivors of an indoctrination process:

I am haunted by these women, their refusal of exceptionality. When asked how they did what they did, they say they were human, no more no less. What if we take them at their word? Then, rather than asking how do we gain the capacity to care, how do we develop a capacity for mutual understanding, how do we learn to take the point of view of the other or overcome the pursuit of self-interest, they prompt us to ask instead: how do we lose the capacity to care, what inhibits our ability to empathize with others, and most painfully, how do we lose the capacity to love? (165).With this as her guiding question, Gilligan challenges us to think about how we might re-formulate education (and society more broadly) to support -- rather than destroy -- "the capacity to love." This brings together notions of education, citizenship, social justice, and peace activism, in a combination that will be familiar to many progressive, counter-cultural educators who have been arguing for holistic education since at least the mid-1960s. One of my disappointments with Resistance was that Gilligan didn't acknowledge or engage with that counter-cultural community (of which there is a fairly active virtual and real-life network here in the northeast United States which she calls home!) within the text. I would have appreciated some evidence that she is at least aware of the dissident educators of the past sixty years (or more) who have insisted that this "feminist ethic of care," this more holistic vision of humanity, be central to our pedagogy as we nurture into adulthood the next generation(s). But one can't have everything!

I'll leave you with one of my favorite passages from the book, which I posted on Tumblr last week with the comment that, while "secure relationships" are obviously not limited to parent-child connections, this is a strong argument that if we want to strengthen marriage and families, we ought to be legalizing (and advocating for!) poly relationships:

The ideal environment for raising children turns out to be not that of the nuclear family but on in which there are at least three secure relationships (gender nonspecific), meaning three relationships that convey the clear message: 'You will be cared for no matter what.' (53)I also want to point out that this is a really strong argument for those of us who plan on not parenting to get involved with people who are parents. Because by being a "secure relationship" person in the life of a child, or children, even (especially?) when they aren't our direct dependents, means we're creating a world in which more adults will be psychologically whole, secure persons. And that's a better world for us all.

*At the very end of Resistance, Gilligan brings in recent research on adolescent boys, which suggests that they, like the adolescent girls whom Gilligan has spent her professional life studying, experience the dissonance and limitations of patriarchy. I'd love to see her (and others) develop this further.

Tuesday, May 22, 2012

booknotes: the morning after

After reading Bodies of Knowledge by Wendy Kline back in March, I decided to follow up one history of women and medicine with another: Heather Munro Prescott's The Morning After: A History of Emergency Contraception in the United States (Rutgers University Press, 2011). Part of the Critical Issues in Health and Medicine series, edited by Rima D. Apple (University of Wisconsin-Madison) and Janet Golden (Rutgers), The Morning After focuses on the development of pharmacological postcoital contraception beginning in the mid-twentieth-century, the ad hoc off-label distribution of contraceptives in emergency situations, and finally the process by which a dedicated emergency contraceptive pill was approved by the FDA for production and marketing. Her narrative ends in the recent past, when emergency contraception was approved for over-the-counter sale to those over the age of seventeen.

Prescott's history is a fairly straightforward narrative which, while valuable in its own way, could have benefited from more analysis and a stronger historical argument. One of the interesting changes Prescott observes over time is in the attitude of feminist/women's health advocates. During the 1970s and 80s were incredibly skeptical (due to a number of high-profile drug failures) about the FDA's interest in, and ability to, ensure the safety of contraceptives and other women's health-related pharmaceuticals. By the 1990s, feminist rhetoric had shifted from safety to one of women's agency: access to emergency contraception became something women had the right to access, once they had been fully and meaningfully informed about their options. This shift from the authority of medical professionals to the authority of women to control their own reproductive capacity is something that I would have liked to see developed further, with particular focus on how it re-formed the politics around emergency contraception.

The other aspect the history of emergency contraception in the U.S. that is touched upon in The Morning After but largely passed over is the shift within the religious right from being fairly neutral about birth control and family planning mid-century (with the exception of the Catholic church) to actually conflating the pharmaceutical birth control options with abortion. Not just in that the two are morally equivalent, but that taking birth control pills (including postcoital birth control) causes you to abort. While medically inaccurate this blurring of the boundary between what is pre-pregnancy birth control and what is abortion expands the backlash on women's reproductive agency exponentially. Birth control advocates can no longer gain allies among anti-abortion activists by arguing (as they did throughout the twentieth century) that the birth control pill will lower the abortion rate by preventing undesired or mis-timed pregnancies. Because "birth control" as become synonymous with "abortion" in many anti-abortion circles. This is a rhetorical shift with on-the-ground consequences, and emergency contraception had no small part to play in this tug-of-war over women's lives. I would have liked to see this particular chapter in the history of EC given a little more time.

Overall, The Morning After is a solid history of a specific type of contraceptive technology, and one which I am glad to have read, as both an historian of feminism, gender, and sexuality, and as someone who tries to stay current in the world of reproductive justice activism.

Prescott's history is a fairly straightforward narrative which, while valuable in its own way, could have benefited from more analysis and a stronger historical argument. One of the interesting changes Prescott observes over time is in the attitude of feminist/women's health advocates. During the 1970s and 80s were incredibly skeptical (due to a number of high-profile drug failures) about the FDA's interest in, and ability to, ensure the safety of contraceptives and other women's health-related pharmaceuticals. By the 1990s, feminist rhetoric had shifted from safety to one of women's agency: access to emergency contraception became something women had the right to access, once they had been fully and meaningfully informed about their options. This shift from the authority of medical professionals to the authority of women to control their own reproductive capacity is something that I would have liked to see developed further, with particular focus on how it re-formed the politics around emergency contraception.

The other aspect the history of emergency contraception in the U.S. that is touched upon in The Morning After but largely passed over is the shift within the religious right from being fairly neutral about birth control and family planning mid-century (with the exception of the Catholic church) to actually conflating the pharmaceutical birth control options with abortion. Not just in that the two are morally equivalent, but that taking birth control pills (including postcoital birth control) causes you to abort. While medically inaccurate this blurring of the boundary between what is pre-pregnancy birth control and what is abortion expands the backlash on women's reproductive agency exponentially. Birth control advocates can no longer gain allies among anti-abortion activists by arguing (as they did throughout the twentieth century) that the birth control pill will lower the abortion rate by preventing undesired or mis-timed pregnancies. Because "birth control" as become synonymous with "abortion" in many anti-abortion circles. This is a rhetorical shift with on-the-ground consequences, and emergency contraception had no small part to play in this tug-of-war over women's lives. I would have liked to see this particular chapter in the history of EC given a little more time.

Overall, The Morning After is a solid history of a specific type of contraceptive technology, and one which I am glad to have read, as both an historian of feminism, gender, and sexuality, and as someone who tries to stay current in the world of reproductive justice activism.

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

booknotes: real live nude girl

After hearing Carol Queen speak back in February, I tracked down a copy of her book of essays on sex-positive culture, Real Live Nude Girl (Cleis Press, 1997; 2003). Nude Girl is a fascinating and deeply personal window into the sexual explorations of a feminist-minded sex nerd from the 1970s into the mid-1990s. The historian in me was particularly interested in the way Queen documents from on the ground the tensions surrounding sexuality and identity that ebbed and flowed in powerful tides through feminist subcultures, queer subcultures, and the lesbian-feminist community. Queen's essays provide a valuable first-person primary-source narrative of those turbulent and exciting times.

On a more personal level, as a child of the 1980s, I have no first-person experience with many of these political tensions, and I marvel at the rigidity and simplicity with which some women approached the intersection of feminist sensibilities with sexual and sensual experience. Enjoying your breasts, having your breasts touched, was consider objectifying -- wait, what? Wearing a skirt made you a bad lesbian? I'm sorry -- come again? I'm sure in thirty or forty years time, people will look back on our own anxieties of the aughts and similarly shake their heads that we made it so fraught for ourselves. (Really? There was a time when asexuality was rejected by some in the queer community? Really? We didn't let trans women into the Michigan Womyn's Music Festival? Say what?) At least, I can only hope it will be so!

I particularly appreciated her essays on being bisexual in the queer subculture, "The Queer in Me," and "Bisexual Perverts Among the Leather Lesbians." As someone who resists hard-and-fast labels (while appreciating the language of identity as a tool for both political organizing and self-discovery), it's always comforting to be reminded that debates over what it means to be a "good" or "bad" queer or feminist are hardly new. "Through a Glass Smudgily: Reflections of a Peep-Show Queen," among others, explores the social aspects of sexual performance and connection. As someone with exhibitionist tendencies, I enjoyed Queen's thoughts about what we get (performer and voyeur alike) from more public manifestations of our sexual selves. In a blend of sexuality and healthcare, "Just Put Your Feet in These Stirrups" is a thoughtful examination of Queen's experience as a live model, teaching ob/gyn residents to perform pelvic exams. Having just read Wendy Kline's historical treatment of pelvic exam practices, Queen's more personal perspective was a delightful parallel to Kline's analysis. And finally, "Dear Mom: A Letter About Whoring" is a heartbreaking essay penned as a letter to her mother after her mother's death. For me, it underscored the sadness of things not said between parents and children in our culture about sexuality and relationships.

I continue to be impressed by Queen's depth and breadth of personal and analytical thought. She blends self-examination and personal experience with the perspective of a scholar and cultural critique. While Real Live Nude Girl was a bit of a trick to find (I ended up ordering a used copy through Amazon), I highly recommend it for the library of anyone with professional or personal interest in the field of human sexuality.

On a more personal level, as a child of the 1980s, I have no first-person experience with many of these political tensions, and I marvel at the rigidity and simplicity with which some women approached the intersection of feminist sensibilities with sexual and sensual experience. Enjoying your breasts, having your breasts touched, was consider objectifying -- wait, what? Wearing a skirt made you a bad lesbian? I'm sorry -- come again? I'm sure in thirty or forty years time, people will look back on our own anxieties of the aughts and similarly shake their heads that we made it so fraught for ourselves. (Really? There was a time when asexuality was rejected by some in the queer community? Really? We didn't let trans women into the Michigan Womyn's Music Festival? Say what?) At least, I can only hope it will be so!

I particularly appreciated her essays on being bisexual in the queer subculture, "The Queer in Me," and "Bisexual Perverts Among the Leather Lesbians." As someone who resists hard-and-fast labels (while appreciating the language of identity as a tool for both political organizing and self-discovery), it's always comforting to be reminded that debates over what it means to be a "good" or "bad" queer or feminist are hardly new. "Through a Glass Smudgily: Reflections of a Peep-Show Queen," among others, explores the social aspects of sexual performance and connection. As someone with exhibitionist tendencies, I enjoyed Queen's thoughts about what we get (performer and voyeur alike) from more public manifestations of our sexual selves. In a blend of sexuality and healthcare, "Just Put Your Feet in These Stirrups" is a thoughtful examination of Queen's experience as a live model, teaching ob/gyn residents to perform pelvic exams. Having just read Wendy Kline's historical treatment of pelvic exam practices, Queen's more personal perspective was a delightful parallel to Kline's analysis. And finally, "Dear Mom: A Letter About Whoring" is a heartbreaking essay penned as a letter to her mother after her mother's death. For me, it underscored the sadness of things not said between parents and children in our culture about sexuality and relationships.

I continue to be impressed by Queen's depth and breadth of personal and analytical thought. She blends self-examination and personal experience with the perspective of a scholar and cultural critique. While Real Live Nude Girl was a bit of a trick to find (I ended up ordering a used copy through Amazon), I highly recommend it for the library of anyone with professional or personal interest in the field of human sexuality.

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

booknotes: an april round-up

So here are a few books I've read recently that I don't have the oomph to give full reviews. The usual disclaimer: The brevity of my review doesn't necessarily indicate the worthiness of the book.

Burke, Phyllis | Gender Shock: Exploding the Myths of Male and Female (Anchor Books, 1996). When Phyllis Burke's son was born, she and her partner found themselves fielding concerned questions about how two lesbians could raise a son without male role models in the family. Burke began by defending her family by talking about all of the men whom her son would connect with in their extended kinship network, but as time went on she found herself wondering why the gender of one's parents should matter when it came to modeling adult behavior. This question led her to explore the scientific and cultural world of normative gender assumptions. Gender Shock's central body of evidence is case histories of children treated by mental health professionals for gender deviance, so consider yourself warned when it comes to rage-inducing narratives in which children are brow-beaten and manipulated into giving up everything from cross-dressing to care-taking, an "excessive" interest in sports or an inclination toward the culinary arts. While some of the most egregious examples of abuse come from the mid-70s and early 80s, Burke makes the point that even in the early 90s children were still being punished for sex and gender deviance, particularly when such non-normative behaviors intersect with other supposed markers for criminality (poverty, non-whiteness, rebelliousness, foster care). While my lay impression is that the professional climate has somewhat improved since then, if anything, the moral panic around children's performance of gender has intensified since the turn of the millennium. Worth reading for those with a professional and/or personal interest in the topic of gender policing.

Kline, Wendy | Bodies of Knowledge: Sexuality, Women's Health and the Second Wave (Chicago University Press, 2010). Kline's brief history of women's health activism during the mid-twentieth century is well researched and thoughtfully written. Rather than attempting a survey of the women's health movement, Kline uses her five chapters to examine specific moments of activism and activist groups: the Boston Women's Health Book Collective, the movement for self-directed pelvic examinations, Chicago-area abortion activism, patient action around the use of Depo-Provera shots as a birth control method, and finally the rise of modern midwifery. Much of Kline's research was done in Boston-area archives, and her case studies are focused in cities along the East Coast and Chicago. This case study approach allows from some fascinating essay-length treatments of specific interactions between feminists and medical professionals / the healthcare industry. Across the chapters, Kline articulates common themes such as the feminist insistence that women were authorities on their own embodied experience, and suspicion of the healthcare industry and medical professionals who were predominantly men, many (though not all) of whom had little time for feminist critiques of medical practice. Discouragingly enough, Kline's central question is why feminist activism around health care was largely unsuccessful in changing mainstream practice. While the book as a whole begs for elaboration on the topic, hopefully Kline's work will serve as inspiration for further research.

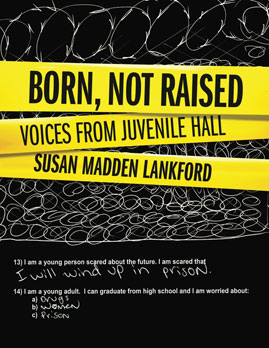

Lankford, Susan Madden | Born, Not Raised: Voices from Juvenile Hall (Humane Exposures, 2012). Voices is the third volume in a trilogy of photo essays in which Lankford documents the experiences of marginal populations: the homeless, women in prison, and now incarcerated children. The book is a collage of voices, including photographs and reproductions of worksheets and essays completed by the youth Lankford worked with in prison alongside Lankford's own reflections, transcribed interviews, and commentary by mental health professionals and workers within the system.The historian in me was frustrated at times with what felt like heavy-handed analysis. The adult commentary meant to interpret young peoples' words and pictures for the reader smacked of condescension toward youth and reader alike. I felt sometimes that the project could have benefited from community-based analysis (e.g. the young people synthesizing and analyzing their experience, and perhaps utilizing the project as a springboard for social change. At the same time, I appreciate Lankford's empathic approach, and her liberal use of primary source materials which allow us some type of access to the inner lives of the marginalized and vulnerable.

Walker, Nancy A. | Shaping Our Mothers' World (University Press of Mississippi, 2000). An English professor, Walker takes an American Studies approach to understanding popular mid-twentieth century women's magazines (i.e. Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, McCall's, Vogue, Mademoiselle) as expressions of both dominant cultural understandings of the domestic and the often ambivalent or contradictory experiences of women themselves negotiating what it meant to be a wife, mother,daughter, unmarried woman, household member, and so forth. She locates these widely-circulated magazines at the hinge-point of "mass culture" (passively-consumed) and "popular culture" (in which one is an active participant). Long-vilified by mid-twentieth-century feminists for disseminating sexist ideals of femininity and family life, Walker suggests that these magazines were far from unified in their ideologies of gender, and that readers often talked back to the editorial, article, and advertising content. I'm only about halfway through this one, but I appreciate Walker's thoughtful re-examination of a popular medium we all think we "know" to have been neo-traditionalist and kyriarchical.

Burke, Phyllis | Gender Shock: Exploding the Myths of Male and Female (Anchor Books, 1996). When Phyllis Burke's son was born, she and her partner found themselves fielding concerned questions about how two lesbians could raise a son without male role models in the family. Burke began by defending her family by talking about all of the men whom her son would connect with in their extended kinship network, but as time went on she found herself wondering why the gender of one's parents should matter when it came to modeling adult behavior. This question led her to explore the scientific and cultural world of normative gender assumptions. Gender Shock's central body of evidence is case histories of children treated by mental health professionals for gender deviance, so consider yourself warned when it comes to rage-inducing narratives in which children are brow-beaten and manipulated into giving up everything from cross-dressing to care-taking, an "excessive" interest in sports or an inclination toward the culinary arts. While some of the most egregious examples of abuse come from the mid-70s and early 80s, Burke makes the point that even in the early 90s children were still being punished for sex and gender deviance, particularly when such non-normative behaviors intersect with other supposed markers for criminality (poverty, non-whiteness, rebelliousness, foster care). While my lay impression is that the professional climate has somewhat improved since then, if anything, the moral panic around children's performance of gender has intensified since the turn of the millennium. Worth reading for those with a professional and/or personal interest in the topic of gender policing.

Kline, Wendy | Bodies of Knowledge: Sexuality, Women's Health and the Second Wave (Chicago University Press, 2010). Kline's brief history of women's health activism during the mid-twentieth century is well researched and thoughtfully written. Rather than attempting a survey of the women's health movement, Kline uses her five chapters to examine specific moments of activism and activist groups: the Boston Women's Health Book Collective, the movement for self-directed pelvic examinations, Chicago-area abortion activism, patient action around the use of Depo-Provera shots as a birth control method, and finally the rise of modern midwifery. Much of Kline's research was done in Boston-area archives, and her case studies are focused in cities along the East Coast and Chicago. This case study approach allows from some fascinating essay-length treatments of specific interactions between feminists and medical professionals / the healthcare industry. Across the chapters, Kline articulates common themes such as the feminist insistence that women were authorities on their own embodied experience, and suspicion of the healthcare industry and medical professionals who were predominantly men, many (though not all) of whom had little time for feminist critiques of medical practice. Discouragingly enough, Kline's central question is why feminist activism around health care was largely unsuccessful in changing mainstream practice. While the book as a whole begs for elaboration on the topic, hopefully Kline's work will serve as inspiration for further research.

Lankford, Susan Madden | Born, Not Raised: Voices from Juvenile Hall (Humane Exposures, 2012). Voices is the third volume in a trilogy of photo essays in which Lankford documents the experiences of marginal populations: the homeless, women in prison, and now incarcerated children. The book is a collage of voices, including photographs and reproductions of worksheets and essays completed by the youth Lankford worked with in prison alongside Lankford's own reflections, transcribed interviews, and commentary by mental health professionals and workers within the system.The historian in me was frustrated at times with what felt like heavy-handed analysis. The adult commentary meant to interpret young peoples' words and pictures for the reader smacked of condescension toward youth and reader alike. I felt sometimes that the project could have benefited from community-based analysis (e.g. the young people synthesizing and analyzing their experience, and perhaps utilizing the project as a springboard for social change. At the same time, I appreciate Lankford's empathic approach, and her liberal use of primary source materials which allow us some type of access to the inner lives of the marginalized and vulnerable.

Walker, Nancy A. | Shaping Our Mothers' World (University Press of Mississippi, 2000). An English professor, Walker takes an American Studies approach to understanding popular mid-twentieth century women's magazines (i.e. Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, McCall's, Vogue, Mademoiselle) as expressions of both dominant cultural understandings of the domestic and the often ambivalent or contradictory experiences of women themselves negotiating what it meant to be a wife, mother,daughter, unmarried woman, household member, and so forth. She locates these widely-circulated magazines at the hinge-point of "mass culture" (passively-consumed) and "popular culture" (in which one is an active participant). Long-vilified by mid-twentieth-century feminists for disseminating sexist ideals of femininity and family life, Walker suggests that these magazines were far from unified in their ideologies of gender, and that readers often talked back to the editorial, article, and advertising content. I'm only about halfway through this one, but I appreciate Walker's thoughtful re-examination of a popular medium we all think we "know" to have been neo-traditionalist and kyriarchical.

Tuesday, January 24, 2012

booknotes: britannia's glory

There are a lot of used bookstores around Boston that have $1 book carts, thus giving rise to that special category of "books one wouldn't have bothered to acquire except they were $1 so why not?" Emily Hamer's Britannia's Glory: A History of Twentieth-Century Lesbians (Cassell, 1996). Not that I lack an interest in the history of English lesbians. In fact, one of my first thoughts skimming the table of contents was, "Oh good! A whole chapter on World War I -- I'll be able to do research for my Downton Abbey fan fiction!" (KarraCrow: "You realize you're unwell, right?). But this isn't the book I'd pick up to do serious historical research. Still, for a dollar? I was totally willing to pick it up for reading on the T this week.

Hamer, whose scholarly background is in philosophy, politics, and economics (Oxford), has written a very readable survey of women's passionate relationships in twentieth-century Britain. I thoroughly enjoyed the chatty, anecdotal chapters that focused on specific women -- famous and not-so-famous alike -- in each period between the suffrage movement and the 1980s. Given that my own knowledge of lesbian activism is U.S.-centric, I appreciated seeing the same period through a slightly different lens, and learning about some new names and publications, particularly in the 1950s-70s, that I know I'll be looking into with more serious historical interest.

The most frustrating thing about the text -- although I wasn't even very irritated, just puzzled by it -- was Hamer's insistence on understanding women's relationships through her own present-day lens of what lesbian relationships looked like, and how lesbian identity is constituted. There has been a long-standing debate in the history of sexuality field about how we understand sexual identities in periods not-our-own. There's a school of thought that sets about "resurrecting" lesbian and gay individuals from the past, on the assumption that such identities (being innate) have always existed, and we can simply uncover what previous historians have overlooked or deliberately denied. I understand this impulse, but as an historian it makes me twitchy: I believe that sexual desires are of our bodies (and therefore to some extent 'ahistorical,' though even that breaks down on some level), but are also inevitably shaped by the historical context in which we live. Thus, to breezily describe women in same-sex relationships as leading "lesbian lives," or someone from the 1910s as being a "butch dyke" is to apply identities from our own repertoire on people who may have performed such roles with a very different self-conception.

Hamer acknowledges this debate, yet ultimately falls back on an ahistorical interpretation, writing, "It is argued that only those women who thought of themselves as lesbians were lesbians. However, this does just [sic] seem wrong: being a lesbian is a theoretically observable aspect of life ... One is a lesbian if the life one lives is a lesbian life" (10). On the one hand, I understand that Hamer is pushing back against people who are reluctant to accept -- without word-for-word proof -- that any same-sex relationships existed before the sexual revolution. Her argument that we hold same-sex relationships to a higher standard of proof than heterosexual relationships is a valid one. At the same time, "lesbian" as we understand the word today is bound by its historically-specific meanings and can't simply serve as a stand-in for "women who had sex with / sustained sexual relationships with other women." Which is how Hamer seems to wish to use it.

Further, her insistence on describing her (often extremely interesting!) historical subjects as "lesbians" leads her to erase or ignore the variability in their sexual desires and lived lives. For example, situating Vita Sackville-West as a "lesbian" leads her to minimize Sackville-West's marriage to Harold Nicolson as a sham, and suggest it was merely an attempt to maintain social respectability. The much more nuanced relationship Sackville-West describes in her own account becomes lost. Likewise, any possibility of women's sexual fluidity or bisexuality is elided. This is probably, in part, a problem of the period in which Britannia's Glory was conceived -- when sexual identities were still being policed at the boundaries to a greater extent than (it is my hope, anyway) we police them today.

I was, perhaps, spoiled by my recent reading of Emma Donoghue's Inseparable (review coming soon), in which Donoghue handles the identity problem quite simply: by focusing on the texture of passion in women's relationships, regardless of how they are named in a particular time and place. Such an approach steps away from our time-bound conceptions of what a woman who desires, and is sexually involved with, other women looks like or conceives of herself -- and focuses on the heart of the matter: the fact that she expressed her sexuality in some form or fashion with other women. For all or part of her life. To my mind, anyway, this is a much more expansive, enduring, and interesting way to study the people who came before us.

Hamer, whose scholarly background is in philosophy, politics, and economics (Oxford), has written a very readable survey of women's passionate relationships in twentieth-century Britain. I thoroughly enjoyed the chatty, anecdotal chapters that focused on specific women -- famous and not-so-famous alike -- in each period between the suffrage movement and the 1980s. Given that my own knowledge of lesbian activism is U.S.-centric, I appreciated seeing the same period through a slightly different lens, and learning about some new names and publications, particularly in the 1950s-70s, that I know I'll be looking into with more serious historical interest.

The most frustrating thing about the text -- although I wasn't even very irritated, just puzzled by it -- was Hamer's insistence on understanding women's relationships through her own present-day lens of what lesbian relationships looked like, and how lesbian identity is constituted. There has been a long-standing debate in the history of sexuality field about how we understand sexual identities in periods not-our-own. There's a school of thought that sets about "resurrecting" lesbian and gay individuals from the past, on the assumption that such identities (being innate) have always existed, and we can simply uncover what previous historians have overlooked or deliberately denied. I understand this impulse, but as an historian it makes me twitchy: I believe that sexual desires are of our bodies (and therefore to some extent 'ahistorical,' though even that breaks down on some level), but are also inevitably shaped by the historical context in which we live. Thus, to breezily describe women in same-sex relationships as leading "lesbian lives," or someone from the 1910s as being a "butch dyke" is to apply identities from our own repertoire on people who may have performed such roles with a very different self-conception.

Hamer acknowledges this debate, yet ultimately falls back on an ahistorical interpretation, writing, "It is argued that only those women who thought of themselves as lesbians were lesbians. However, this does just [sic] seem wrong: being a lesbian is a theoretically observable aspect of life ... One is a lesbian if the life one lives is a lesbian life" (10). On the one hand, I understand that Hamer is pushing back against people who are reluctant to accept -- without word-for-word proof -- that any same-sex relationships existed before the sexual revolution. Her argument that we hold same-sex relationships to a higher standard of proof than heterosexual relationships is a valid one. At the same time, "lesbian" as we understand the word today is bound by its historically-specific meanings and can't simply serve as a stand-in for "women who had sex with / sustained sexual relationships with other women." Which is how Hamer seems to wish to use it.

Further, her insistence on describing her (often extremely interesting!) historical subjects as "lesbians" leads her to erase or ignore the variability in their sexual desires and lived lives. For example, situating Vita Sackville-West as a "lesbian" leads her to minimize Sackville-West's marriage to Harold Nicolson as a sham, and suggest it was merely an attempt to maintain social respectability. The much more nuanced relationship Sackville-West describes in her own account becomes lost. Likewise, any possibility of women's sexual fluidity or bisexuality is elided. This is probably, in part, a problem of the period in which Britannia's Glory was conceived -- when sexual identities were still being policed at the boundaries to a greater extent than (it is my hope, anyway) we police them today.

I was, perhaps, spoiled by my recent reading of Emma Donoghue's Inseparable (review coming soon), in which Donoghue handles the identity problem quite simply: by focusing on the texture of passion in women's relationships, regardless of how they are named in a particular time and place. Such an approach steps away from our time-bound conceptions of what a woman who desires, and is sexually involved with, other women looks like or conceives of herself -- and focuses on the heart of the matter: the fact that she expressed her sexuality in some form or fashion with other women. For all or part of her life. To my mind, anyway, this is a much more expansive, enduring, and interesting way to study the people who came before us.

Tuesday, January 10, 2012

booknotes: deviations

|

| find table of contents here |

Deviations is arranged in chronological order, beginning with Rubin's first attempt to construct a theory of gender relations rooted in anthropological methodology -- "The Traffic in Women: Notes on the 'Political Economy' of Sex," written and revised between the late 60s and early 70s and first published in 1975. It is very much an artifact of its time and to be honest I bogged in this piece for the better part of a month after joyfully burning my way through the eminently readable introduction. Perhaps recognizing the opacity of "Traffic," Rubin includes a piece reflecting back on the writing and reception of the original piece and includes it in the anthology -- something she does several times throughout the book to great effect. After "Traffic" and its contextual essay comes a much more accessible piece on the English author Renee Vivien, originally written as an introduction and afterward to a new edition of Vivien's A Woman Appeared Before Me, which is a fictionalized account of her tumultuous relationship with fellow author and outspoken lesbian-feminist Natalie Barney.

By the late 70s, Rubin was deep into the ethnographic research for her dissertation on the gay male leather bars of San Francisco, for which she received her PhD in 1994 from the University of Michigan. The majority of pieces in Deviations, therefore, wrestle not with the politics of gender or specifically lesbian-feminist history, but the politics of sexual practices, sexual subcultures, and the relationship between feminist theory and practice and human sexuality. As someone who is, like Rubin, committed to understanding the world through both a feminist and queer lens, I really appreciate her determination to remain engaged in feminist thinking and activism even as she was reviled by certain segments of the feminist movement for her "deviations" in sexual practice, and her openness to thinking about sexual subcultures that -- for many in our culture, even many self-identified feminists -- elicit feelings of disgust and generate sex panics. While the "porn wars" of the 1980s are largely a thing of the past, feminists continue to find sexuality, sexual desires, sexual practices, and sexual fantasy (whether private or shared via erotica/porn of whatever medium) incredibly difficult to speak about. Rubin calls upon us to think with greater clarity about the politics of sex, and how we police other peoples' sexual activities, many of them consensual, simply because we find them distasteful.

Particularly controversial, I imagine, are Rubin's writings on cross-generational sexual activities and children's sexuality. Coming out of the BDSM framework, Rubin foregrounds the basic ethic of consent and argues that children have just as much right to consent to sexual activities as adults. Furthermore, within the framework of 1980s anti-pornography legislation, she emphasizes the difference between fantasy/desire and reality/action (that is: depiction of non-consensual sex in the context of a fantasy does not equal non-consensual sex and shouldn't be treated in the same fashion). This leads her to speak up in defense of adults who express sexual desire for young people (but don't act on that desire), and also to suggest that not all instances of underage/overage sexual intimacy should be treated as sexual abuse or assault. Read in tandem with Rubin's insistence that we take children seriously as human beings with the right to sexual knowledge, this advocacy is clearly not a call to minimize the trauma of sexual violence (at whatever age) or a glossing over of age-related power dynamics. "The notion that sex per se is harmful to the young has been chiseled into extensive social and legal structures," she writes, "designed to insulate minors from sexual knowledge and experience" (159). Like Judith Levine in Harmful to Minors (2002), Rubin argues that our cultural insistence on keeping young people separated from sexuality and sensuality -- with a vigilance that often spills over into panic and hysteria -- does little to protect them from sexual violence and exploitation while cutting them off from the means to conduct their own (safe, consensual) sexual explorations or name and resist the violence and exploitation that may come their way. Sexting panics anyone? The Purity Myth?

Overall, I highly recommend Deviations to anyone interested in the development of feminist and sexual political theory and practice over the last forty years -- if nothing else, Rubin's bibliography has already given me a handful of other thinkers whose books and articles I wish to pursue.

Cross-posted at the feminist librarian and The Pursuit of Harpyness.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)