So here are a few books I've read recently that I don't have the oomph to give full reviews. The usual disclaimer: The brevity of my review doesn't necessarily indicate the worthiness of the book.

Burke, Phyllis | Gender Shock: Exploding the Myths of Male and Female (Anchor Books, 1996). When Phyllis Burke's son was born, she and her partner found themselves fielding concerned questions about how two lesbians could raise a son without male role models in the family. Burke began by defending her family by talking about all of the men whom her son would connect with in their extended kinship network, but as time went on she found herself wondering why the gender of one's parents should matter when it came to modeling adult behavior. This question led her to explore the scientific and cultural world of normative gender assumptions. Gender Shock's central body of evidence is case histories of children treated by mental health professionals for gender deviance, so consider yourself warned when it comes to rage-inducing narratives in which children are brow-beaten and manipulated into giving up everything from cross-dressing to care-taking, an "excessive" interest in sports or an inclination toward the culinary arts. While some of the most egregious examples of abuse come from the mid-70s and early 80s, Burke makes the point that even in the early 90s children were still being punished for sex and gender deviance, particularly when such non-normative behaviors intersect with other supposed markers for criminality (poverty, non-whiteness, rebelliousness, foster care). While my lay impression is that the professional climate has somewhat improved since then, if anything, the moral panic around children's performance of gender has intensified since the turn of the millennium. Worth reading for those with a professional and/or personal interest in the topic of gender policing.

Kline, Wendy | Bodies of Knowledge: Sexuality, Women's Health and the Second Wave (Chicago University Press, 2010). Kline's brief history of women's health activism during the mid-twentieth century is well researched and thoughtfully written. Rather than attempting a survey of the women's health movement, Kline uses her five chapters to examine specific moments of activism and activist groups: the Boston Women's Health Book Collective, the movement for self-directed pelvic examinations, Chicago-area abortion activism, patient action around the use of Depo-Provera shots as a birth control method, and finally the rise of modern midwifery. Much of Kline's research was done in Boston-area archives, and her case studies are focused in cities along the East Coast and Chicago. This case study approach allows from some fascinating essay-length treatments of specific interactions between feminists and medical professionals / the healthcare industry. Across the chapters, Kline articulates common themes such as the feminist insistence that women were authorities on their own embodied experience, and suspicion of the healthcare industry and medical professionals who were predominantly men, many (though not all) of whom had little time for feminist critiques of medical practice. Discouragingly enough, Kline's central question is why feminist activism around health care was largely unsuccessful in changing mainstream practice. While the book as a whole begs for elaboration on the topic, hopefully Kline's work will serve as inspiration for further research.

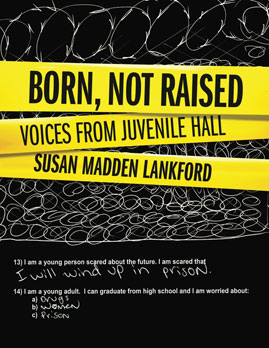

Lankford, Susan Madden | Born, Not Raised: Voices from Juvenile Hall (Humane Exposures, 2012). Voices is the third volume in a trilogy of photo essays in which Lankford documents the experiences of marginal populations: the homeless, women in prison, and now incarcerated children. The book is a collage of voices, including photographs and reproductions of worksheets and essays completed by the youth Lankford worked with in prison alongside Lankford's own reflections, transcribed interviews, and commentary by mental health professionals and workers within the system.The historian in me was frustrated at times with what felt like heavy-handed analysis. The adult commentary meant to interpret young peoples' words and pictures for the reader smacked of condescension toward youth and reader alike. I felt sometimes that the project could have benefited from community-based analysis (e.g. the young people synthesizing and analyzing their experience, and perhaps utilizing the project as a springboard for social change. At the same time, I appreciate Lankford's empathic approach, and her liberal use of primary source materials which allow us some type of access to the inner lives of the marginalized and vulnerable.

Walker, Nancy A. | Shaping Our Mothers' World (University Press of Mississippi, 2000). An English professor, Walker takes an American Studies approach to understanding popular mid-twentieth century women's magazines (i.e. Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, McCall's, Vogue, Mademoiselle) as expressions of both dominant cultural understandings of the domestic and the often ambivalent or contradictory experiences of women themselves negotiating what it meant to be a wife, mother,daughter, unmarried woman, household member, and so forth. She locates these widely-circulated magazines at the hinge-point of "mass culture" (passively-consumed) and "popular culture" (in which one is an active participant). Long-vilified by mid-twentieth-century feminists for disseminating sexist ideals of femininity and family life, Walker suggests that these magazines were far from unified in their ideologies of gender, and that readers often talked back to the editorial, article, and advertising content. I'm only about halfway through this one, but I appreciate Walker's thoughtful re-examination of a popular medium we all think we "know" to have been neo-traditionalist and kyriarchical.

No comments:

Post a Comment