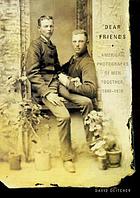

A colleague of mine at work recently passed along a copy of David Deitcher's Dear Friend: American Photographs of Men Together, 18401-1918 (Abrams, 2001). This is a fascinating photo essay book which gathers together early American portraits of "men together," captured by the camera in intimate poses. For the most part, these are formal portraits, the individuals arranged (or arranging themselves) with body language that reads to us, today, as "couple." Deitcher, an art historian and self-identified gay man, became intrigued with this genre of photographs after a student who attended one of his guest lectures showed him several examples of such images the student had purchased at flea markets. Intrigued by the ease with which the subjects seemed to pose together, their bodies intertwined, Deitcher began to search for other examples of nineteenth-century images of male couples or male groups posing together with affection. Dear Friend reproduces many of these examples, most of them of anonymous subjects, the specific context of their creation lost to time.

Accompanying the images is Deitcher's commentary, telling the story of his quest for the photographs and their modern-day reception, as well as analysis of the images both as art and historical artifact. "It is one thing to describe what such photographs represent (for the gay man who collects them with such avidity), quite another to claim to know with any degree of historical precision what it is that they depict" (76). Throughout the book Deitcher attempts to keep in tension -- not wholly successfully -- the notions that these images can, and do, represent to modern queer individuals the universality of same-sex desire while at the same time we can never know with certainty the quality of emotion that brought these photographic subjects together in the frame. At times, Deitcher over-eggs the cake in his attempt to push back against historians' insistence that the past is a foreign country. Feeling same-sex desire is erased or denied in scholars' formulation of "passionate friendship," he pushes us to imagine that at least some of these photographs do, in fact, depict men who were in each others' pants on a regular basis. This I'm very willing to believe; I'm less willing to see historians of sexuality as homophobic in their insistence that we back away from inscribing twenty or twenty-first century notions of sexual identity onto the past.

Nonetheless, this is a fascinating collection of images that encourage us to historicize our own notions of heteronormative behavior, as well as challenge our collective memory of a straight past.

No comments:

Post a Comment