After hearing Carol Queen speak back in February, I tracked down a copy of her book of essays on sex-positive culture, Real Live Nude Girl (Cleis Press, 1997; 2003). Nude Girl is a fascinating and deeply personal window into the sexual explorations of a feminist-minded sex nerd from the 1970s into the mid-1990s. The historian in me was particularly interested in the way Queen documents from on the ground the tensions surrounding sexuality and identity that ebbed and flowed in powerful tides through feminist subcultures, queer subcultures, and the lesbian-feminist community. Queen's essays provide a valuable first-person primary-source narrative of those turbulent and exciting times.

On a more personal level, as a child of the 1980s, I have no first-person experience with many of these political tensions, and I marvel at the rigidity and simplicity with which some women approached the intersection of feminist sensibilities with sexual and sensual experience. Enjoying your breasts, having your breasts touched, was consider objectifying -- wait, what? Wearing a skirt made you a bad lesbian? I'm sorry -- come again? I'm sure in thirty or forty years time, people will look back on our own anxieties of the aughts and similarly shake their heads that we made it so fraught for ourselves. (Really? There was a time when asexuality was rejected by some in the queer community? Really? We didn't let trans women into the Michigan Womyn's Music Festival? Say what?) At least, I can only hope it will be so!

I particularly appreciated her essays on being bisexual in the queer subculture, "The Queer in Me," and "Bisexual Perverts Among the Leather Lesbians." As someone who resists hard-and-fast labels (while appreciating the language of identity as a tool for both political organizing and self-discovery), it's always comforting to be reminded that debates over what it means to be a "good" or "bad" queer or feminist are hardly new. "Through a Glass Smudgily: Reflections of a Peep-Show Queen," among others, explores the social aspects of sexual performance and connection. As someone with exhibitionist tendencies, I enjoyed Queen's thoughts about what we get (performer and voyeur alike) from more public manifestations of our sexual selves. In a blend of sexuality and healthcare, "Just Put Your Feet in These Stirrups" is a thoughtful examination of Queen's experience as a live model, teaching ob/gyn residents to perform pelvic exams. Having just read Wendy Kline's historical treatment of pelvic exam practices, Queen's more personal perspective was a delightful parallel to Kline's analysis. And finally, "Dear Mom: A Letter About Whoring" is a heartbreaking essay penned as a letter to her mother after her mother's death. For me, it underscored the sadness of things not said between parents and children in our culture about sexuality and relationships.

I continue to be impressed by Queen's depth and breadth of personal and analytical thought. She blends self-examination and personal experience with the perspective of a scholar and cultural critique. While Real Live Nude Girl was a bit of a trick to find (I ended up ordering a used copy through Amazon), I highly recommend it for the library of anyone with professional or personal interest in the field of human sexuality.

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

Tuesday, April 17, 2012

booknotes: dear friend

A colleague of mine at work recently passed along a copy of David Deitcher's Dear Friend: American Photographs of Men Together, 18401-1918 (Abrams, 2001). This is a fascinating photo essay book which gathers together early American portraits of "men together," captured by the camera in intimate poses. For the most part, these are formal portraits, the individuals arranged (or arranging themselves) with body language that reads to us, today, as "couple." Deitcher, an art historian and self-identified gay man, became intrigued with this genre of photographs after a student who attended one of his guest lectures showed him several examples of such images the student had purchased at flea markets. Intrigued by the ease with which the subjects seemed to pose together, their bodies intertwined, Deitcher began to search for other examples of nineteenth-century images of male couples or male groups posing together with affection. Dear Friend reproduces many of these examples, most of them of anonymous subjects, the specific context of their creation lost to time.

Accompanying the images is Deitcher's commentary, telling the story of his quest for the photographs and their modern-day reception, as well as analysis of the images both as art and historical artifact. "It is one thing to describe what such photographs represent (for the gay man who collects them with such avidity), quite another to claim to know with any degree of historical precision what it is that they depict" (76). Throughout the book Deitcher attempts to keep in tension -- not wholly successfully -- the notions that these images can, and do, represent to modern queer individuals the universality of same-sex desire while at the same time we can never know with certainty the quality of emotion that brought these photographic subjects together in the frame. At times, Deitcher over-eggs the cake in his attempt to push back against historians' insistence that the past is a foreign country. Feeling same-sex desire is erased or denied in scholars' formulation of "passionate friendship," he pushes us to imagine that at least some of these photographs do, in fact, depict men who were in each others' pants on a regular basis. This I'm very willing to believe; I'm less willing to see historians of sexuality as homophobic in their insistence that we back away from inscribing twenty or twenty-first century notions of sexual identity onto the past.

Nonetheless, this is a fascinating collection of images that encourage us to historicize our own notions of heteronormative behavior, as well as challenge our collective memory of a straight past.

Accompanying the images is Deitcher's commentary, telling the story of his quest for the photographs and their modern-day reception, as well as analysis of the images both as art and historical artifact. "It is one thing to describe what such photographs represent (for the gay man who collects them with such avidity), quite another to claim to know with any degree of historical precision what it is that they depict" (76). Throughout the book Deitcher attempts to keep in tension -- not wholly successfully -- the notions that these images can, and do, represent to modern queer individuals the universality of same-sex desire while at the same time we can never know with certainty the quality of emotion that brought these photographic subjects together in the frame. At times, Deitcher over-eggs the cake in his attempt to push back against historians' insistence that the past is a foreign country. Feeling same-sex desire is erased or denied in scholars' formulation of "passionate friendship," he pushes us to imagine that at least some of these photographs do, in fact, depict men who were in each others' pants on a regular basis. This I'm very willing to believe; I'm less willing to see historians of sexuality as homophobic in their insistence that we back away from inscribing twenty or twenty-first century notions of sexual identity onto the past.

Nonetheless, this is a fascinating collection of images that encourage us to historicize our own notions of heteronormative behavior, as well as challenge our collective memory of a straight past.

Thursday, April 12, 2012

Is Such a Thing Possible?

I never wanted to be a Supernatural fan.

I never planned to have a Tumblr full of pictures of Jensen Ackles and Misha Collins.

I did not start out to be a Sherlock fan.

It was not down in my datebook to be bitterly disappointed by the second season.

I did not have it in mind to become a Stargate: Atlantis fan.

I really had other things to do besides become obsessed with John Sheppard/Rodney McKay fanfic.

So what the hell happened?

Is there such a thing as a "reluctant fan"? Because if there is: I'm it. I really don't want to care about the Winchesters or their ridiculous Plot Convenience Playhouse angel! I feel I should email Eric Kripke and tell him, 'I didn't agree to this. Please, get your story out of my head.'

But did I then somehow agree to my other fandoms? Because I'd never dream of emailing Steven Moffatt with a similar request! George Lucas sleeps safely at night knowing I will never ask him to get his story out of my synapses.

On the other hand, I've been a fan of those two universes for so long that they're just kind of...there. They're in my head, like Arthur Dent and the continents of Earth as mental furniture and there's another one! I remember reading The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy when I was, I think, 9 or 10 or so: didn't understand a bloody thing that was going on and I was crying I was laughing so hard. Why was "petit fours lolloping off into the distance" so funny? No idea. Didn't even know what a petit four was. Knew it was pretty fucking funny all the same.

I think I resent my fandom of Supernatural, Sherlock, et. al. a little bit because I tend to become -- ahem -- somewhat emotionally invested in my fandoms. Well, don't we all, really? Or we'd find something else to do with our time, right? And I picked up all of the above as a break from the things I was emotionally invested in.

The Doctor being sealed into the Pandorica? That's okay: Dean's probably doing something charmingly unfortunate and oh look! gym socks.

But it doesn't work, does it? Anything interesting enough to keep my attention for more than a season is probably good enough -- even if only borderline good enough! -- to get my involvement...even if I don't notice it happening.

Hm. This is a thought I had hoped would work itself out as I started writing but it didn't quite work. To be continued, I think...

I never planned to have a Tumblr full of pictures of Jensen Ackles and Misha Collins.

I did not start out to be a Sherlock fan.

It was not down in my datebook to be bitterly disappointed by the second season.

I did not have it in mind to become a Stargate: Atlantis fan.

I really had other things to do besides become obsessed with John Sheppard/Rodney McKay fanfic.

So what the hell happened?

Is there such a thing as a "reluctant fan"? Because if there is: I'm it. I really don't want to care about the Winchesters or their ridiculous Plot Convenience Playhouse angel! I feel I should email Eric Kripke and tell him, 'I didn't agree to this. Please, get your story out of my head.'

But did I then somehow agree to my other fandoms? Because I'd never dream of emailing Steven Moffatt with a similar request! George Lucas sleeps safely at night knowing I will never ask him to get his story out of my synapses.

On the other hand, I've been a fan of those two universes for so long that they're just kind of...there. They're in my head, like Arthur Dent and the continents of Earth as mental furniture and there's another one! I remember reading The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy when I was, I think, 9 or 10 or so: didn't understand a bloody thing that was going on and I was crying I was laughing so hard. Why was "petit fours lolloping off into the distance" so funny? No idea. Didn't even know what a petit four was. Knew it was pretty fucking funny all the same.

I think I resent my fandom of Supernatural, Sherlock, et. al. a little bit because I tend to become -- ahem -- somewhat emotionally invested in my fandoms. Well, don't we all, really? Or we'd find something else to do with our time, right? And I picked up all of the above as a break from the things I was emotionally invested in.

The Doctor being sealed into the Pandorica? That's okay: Dean's probably doing something charmingly unfortunate and oh look! gym socks.

But it doesn't work, does it? Anything interesting enough to keep my attention for more than a season is probably good enough -- even if only borderline good enough! -- to get my involvement...even if I don't notice it happening.

Hm. This is a thought I had hoped would work itself out as I started writing but it didn't quite work. To be continued, I think...

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

booknotes: an april round-up

So here are a few books I've read recently that I don't have the oomph to give full reviews. The usual disclaimer: The brevity of my review doesn't necessarily indicate the worthiness of the book.

Burke, Phyllis | Gender Shock: Exploding the Myths of Male and Female (Anchor Books, 1996). When Phyllis Burke's son was born, she and her partner found themselves fielding concerned questions about how two lesbians could raise a son without male role models in the family. Burke began by defending her family by talking about all of the men whom her son would connect with in their extended kinship network, but as time went on she found herself wondering why the gender of one's parents should matter when it came to modeling adult behavior. This question led her to explore the scientific and cultural world of normative gender assumptions. Gender Shock's central body of evidence is case histories of children treated by mental health professionals for gender deviance, so consider yourself warned when it comes to rage-inducing narratives in which children are brow-beaten and manipulated into giving up everything from cross-dressing to care-taking, an "excessive" interest in sports or an inclination toward the culinary arts. While some of the most egregious examples of abuse come from the mid-70s and early 80s, Burke makes the point that even in the early 90s children were still being punished for sex and gender deviance, particularly when such non-normative behaviors intersect with other supposed markers for criminality (poverty, non-whiteness, rebelliousness, foster care). While my lay impression is that the professional climate has somewhat improved since then, if anything, the moral panic around children's performance of gender has intensified since the turn of the millennium. Worth reading for those with a professional and/or personal interest in the topic of gender policing.

Kline, Wendy | Bodies of Knowledge: Sexuality, Women's Health and the Second Wave (Chicago University Press, 2010). Kline's brief history of women's health activism during the mid-twentieth century is well researched and thoughtfully written. Rather than attempting a survey of the women's health movement, Kline uses her five chapters to examine specific moments of activism and activist groups: the Boston Women's Health Book Collective, the movement for self-directed pelvic examinations, Chicago-area abortion activism, patient action around the use of Depo-Provera shots as a birth control method, and finally the rise of modern midwifery. Much of Kline's research was done in Boston-area archives, and her case studies are focused in cities along the East Coast and Chicago. This case study approach allows from some fascinating essay-length treatments of specific interactions between feminists and medical professionals / the healthcare industry. Across the chapters, Kline articulates common themes such as the feminist insistence that women were authorities on their own embodied experience, and suspicion of the healthcare industry and medical professionals who were predominantly men, many (though not all) of whom had little time for feminist critiques of medical practice. Discouragingly enough, Kline's central question is why feminist activism around health care was largely unsuccessful in changing mainstream practice. While the book as a whole begs for elaboration on the topic, hopefully Kline's work will serve as inspiration for further research.

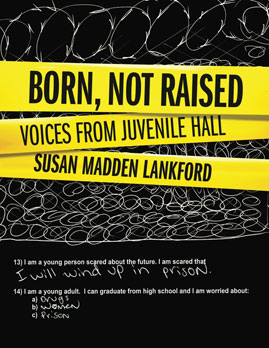

Lankford, Susan Madden | Born, Not Raised: Voices from Juvenile Hall (Humane Exposures, 2012). Voices is the third volume in a trilogy of photo essays in which Lankford documents the experiences of marginal populations: the homeless, women in prison, and now incarcerated children. The book is a collage of voices, including photographs and reproductions of worksheets and essays completed by the youth Lankford worked with in prison alongside Lankford's own reflections, transcribed interviews, and commentary by mental health professionals and workers within the system.The historian in me was frustrated at times with what felt like heavy-handed analysis. The adult commentary meant to interpret young peoples' words and pictures for the reader smacked of condescension toward youth and reader alike. I felt sometimes that the project could have benefited from community-based analysis (e.g. the young people synthesizing and analyzing their experience, and perhaps utilizing the project as a springboard for social change. At the same time, I appreciate Lankford's empathic approach, and her liberal use of primary source materials which allow us some type of access to the inner lives of the marginalized and vulnerable.

Walker, Nancy A. | Shaping Our Mothers' World (University Press of Mississippi, 2000). An English professor, Walker takes an American Studies approach to understanding popular mid-twentieth century women's magazines (i.e. Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, McCall's, Vogue, Mademoiselle) as expressions of both dominant cultural understandings of the domestic and the often ambivalent or contradictory experiences of women themselves negotiating what it meant to be a wife, mother,daughter, unmarried woman, household member, and so forth. She locates these widely-circulated magazines at the hinge-point of "mass culture" (passively-consumed) and "popular culture" (in which one is an active participant). Long-vilified by mid-twentieth-century feminists for disseminating sexist ideals of femininity and family life, Walker suggests that these magazines were far from unified in their ideologies of gender, and that readers often talked back to the editorial, article, and advertising content. I'm only about halfway through this one, but I appreciate Walker's thoughtful re-examination of a popular medium we all think we "know" to have been neo-traditionalist and kyriarchical.

Burke, Phyllis | Gender Shock: Exploding the Myths of Male and Female (Anchor Books, 1996). When Phyllis Burke's son was born, she and her partner found themselves fielding concerned questions about how two lesbians could raise a son without male role models in the family. Burke began by defending her family by talking about all of the men whom her son would connect with in their extended kinship network, but as time went on she found herself wondering why the gender of one's parents should matter when it came to modeling adult behavior. This question led her to explore the scientific and cultural world of normative gender assumptions. Gender Shock's central body of evidence is case histories of children treated by mental health professionals for gender deviance, so consider yourself warned when it comes to rage-inducing narratives in which children are brow-beaten and manipulated into giving up everything from cross-dressing to care-taking, an "excessive" interest in sports or an inclination toward the culinary arts. While some of the most egregious examples of abuse come from the mid-70s and early 80s, Burke makes the point that even in the early 90s children were still being punished for sex and gender deviance, particularly when such non-normative behaviors intersect with other supposed markers for criminality (poverty, non-whiteness, rebelliousness, foster care). While my lay impression is that the professional climate has somewhat improved since then, if anything, the moral panic around children's performance of gender has intensified since the turn of the millennium. Worth reading for those with a professional and/or personal interest in the topic of gender policing.

Kline, Wendy | Bodies of Knowledge: Sexuality, Women's Health and the Second Wave (Chicago University Press, 2010). Kline's brief history of women's health activism during the mid-twentieth century is well researched and thoughtfully written. Rather than attempting a survey of the women's health movement, Kline uses her five chapters to examine specific moments of activism and activist groups: the Boston Women's Health Book Collective, the movement for self-directed pelvic examinations, Chicago-area abortion activism, patient action around the use of Depo-Provera shots as a birth control method, and finally the rise of modern midwifery. Much of Kline's research was done in Boston-area archives, and her case studies are focused in cities along the East Coast and Chicago. This case study approach allows from some fascinating essay-length treatments of specific interactions between feminists and medical professionals / the healthcare industry. Across the chapters, Kline articulates common themes such as the feminist insistence that women were authorities on their own embodied experience, and suspicion of the healthcare industry and medical professionals who were predominantly men, many (though not all) of whom had little time for feminist critiques of medical practice. Discouragingly enough, Kline's central question is why feminist activism around health care was largely unsuccessful in changing mainstream practice. While the book as a whole begs for elaboration on the topic, hopefully Kline's work will serve as inspiration for further research.

Lankford, Susan Madden | Born, Not Raised: Voices from Juvenile Hall (Humane Exposures, 2012). Voices is the third volume in a trilogy of photo essays in which Lankford documents the experiences of marginal populations: the homeless, women in prison, and now incarcerated children. The book is a collage of voices, including photographs and reproductions of worksheets and essays completed by the youth Lankford worked with in prison alongside Lankford's own reflections, transcribed interviews, and commentary by mental health professionals and workers within the system.The historian in me was frustrated at times with what felt like heavy-handed analysis. The adult commentary meant to interpret young peoples' words and pictures for the reader smacked of condescension toward youth and reader alike. I felt sometimes that the project could have benefited from community-based analysis (e.g. the young people synthesizing and analyzing their experience, and perhaps utilizing the project as a springboard for social change. At the same time, I appreciate Lankford's empathic approach, and her liberal use of primary source materials which allow us some type of access to the inner lives of the marginalized and vulnerable.

Walker, Nancy A. | Shaping Our Mothers' World (University Press of Mississippi, 2000). An English professor, Walker takes an American Studies approach to understanding popular mid-twentieth century women's magazines (i.e. Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, McCall's, Vogue, Mademoiselle) as expressions of both dominant cultural understandings of the domestic and the often ambivalent or contradictory experiences of women themselves negotiating what it meant to be a wife, mother,daughter, unmarried woman, household member, and so forth. She locates these widely-circulated magazines at the hinge-point of "mass culture" (passively-consumed) and "popular culture" (in which one is an active participant). Long-vilified by mid-twentieth-century feminists for disseminating sexist ideals of femininity and family life, Walker suggests that these magazines were far from unified in their ideologies of gender, and that readers often talked back to the editorial, article, and advertising content. I'm only about halfway through this one, but I appreciate Walker's thoughtful re-examination of a popular medium we all think we "know" to have been neo-traditionalist and kyriarchical.

Tuesday, April 3, 2012

booknotes: in search of gay america + art and sex in greenwich village

In March, I read two books about the gay and lesbian subculture of the 70s and 80s: Neil Miller's In Search of Gay America: Women and Men in a Time of Change (Atlantic, 1989) and Felice Picano's Art and Sex in Greenwich Village: Gay Literary Life After Stonewall (Carroll & Graf, 2007). Both of these accounts straddle the line between history and memoir, or in Miller's case journalism and memoir. Like so many highly personal accounts of the recent past, these books will serve as fascinating primary sources for future historians who not only want to know what happened within the queer subculture of the late twentieth century, but what those individuals involved in that subculture made of it. How they understood the political and cultural tensions that eddied around their lives, what political battles held meaning for them, what cultural trends were celebrated or mourned, and what they saw when they looked toward a future for gay and lesbian culture and politics.*

In Search of Gay America is a book that grew out of Miller's travels throughout the United States interviewing gay and lesbian folks about their lives. He's particularly interested in relatively levels of "outness" in rural, suburban, and urban areas, as well as different geographical regions -- are queer folks living in Minnesota more or less likely to be out than those living in Missouri? Alabama? Massachusetts? What are their connections to both the queer community and their local community? Do they live openly with a partner, or go away to the big city once a month to party at the gay bar or women's center? If they attend church, are they open about their sexuality and if so how did the congregation react? Aware that "gay America" is often imagined as existing solely in urban locales, Miller purposefully sought out interviewees in more rural locations, as well as talking with people in such iconic queer spaces as San Francisco.

His portraits are memorable and contain a healthy diversity -- though I doubt his sample would stand up to any sort of statistical analysis. We meet gay dairy farmers, lesbian homesteaders, a lesbian minister put on trial for her relationship with another minister's ex-wife, and a gay mayor of a small town in Missouri, and even such high-profile queer folk as Armistead Maupin and Susie Bright. For obvious reasons, I enjoyed the chapter on sex-positive lesbians and the porn wars, in which Miller adopts the bemused tone of an outsider trying to understand the complex dynamics of a turbulent family reunion. While he falls into some unfortunate stereotypes of 1970s lesbian identity (i.e. that until the 80s most lesbians were content not to have much sex), his account does highlight the way in which gay male and lesbian subcultures were so divergent at that point (in the mid-80s) that Miller himself struggled to find mutual points of reference.

His portraits are memorable and contain a healthy diversity -- though I doubt his sample would stand up to any sort of statistical analysis. We meet gay dairy farmers, lesbian homesteaders, a lesbian minister put on trial for her relationship with another minister's ex-wife, and a gay mayor of a small town in Missouri, and even such high-profile queer folk as Armistead Maupin and Susie Bright. For obvious reasons, I enjoyed the chapter on sex-positive lesbians and the porn wars, in which Miller adopts the bemused tone of an outsider trying to understand the complex dynamics of a turbulent family reunion. While he falls into some unfortunate stereotypes of 1970s lesbian identity (i.e. that until the 80s most lesbians were content not to have much sex), his account does highlight the way in which gay male and lesbian subcultures were so divergent at that point (in the mid-80s) that Miller himself struggled to find mutual points of reference.

Art and Sex is Picano's anecdotal history of the Gay Presses of New York, beginning with his own SeaHorse Press (1977) and moving through the consolidation of GPNY (1981) into the late 1980s. It's a rambling narrative, mixing highly amusing -- and often pointed -- snapshots of his interactions with various authors, artists, and other members of the gay literary scene in with a more chronological assembly of factual details. The overarching narrative is one charting the movement of queer literature from the margins to the (slightly more) mainstream: from a time when you had to know the bookstore from which to special order titles, to a time when major publishing houses were seeking to re-issue gay classics. One of my favorite anecdotes involved a bookseller of the old guard who refused to stock a GPNY title because he deemed it not gay enough. This same bookseller was also extremely lax about his accounts, and when Picano called him up about the outstanding balance essentially told Picano he should be grateful the bookstore was willing to stock his titles at all. While Picano doesn't explicitly make the connection between this interaction and the mainstreaming of queer culture (at least in New York) post-Stonewall, it is clear that there has been a generational shift in expectations between when the bookstore owner set up shop and Picano began publishing -- no longer were publishers of "gay" literature held hostage in quite the same way to the whims of distributors.

Picano also, inevitably, touches on the way AIDS ravaged his circle of friends and acquaintances during the 80s, and to a lesser extent writes about the tension between gay (male) presses and the underground lesbian presses, particularly as they connected to the broader subculture of lesbian-feminist separatism. He writes with frustration about the double-bind he experienced when literary events he organized would be accused of lacking female representation -- but the women he asked to participate would refuse on principle because the event was not organized by their own people.

All in all, I'd say Miller's book is of more general interest than Picano's, but that both will be of use to anyone with either a casual or scholarly interest in first-person narratives of queer subcultures in twentieth-century America.

*I'm using "gay and lesbian" quite deliberately because for the most part both authors are dealing specifically with gay and lesbian-identified people, not a more polyglot group of queer folks. Their framework is rooted very much in the political identities of the 70s-90s, not the increasingly fluid understandings of sexuality that have seeped into our twenty-first century identities (Jack Harkness would be proud!).

In Search of Gay America is a book that grew out of Miller's travels throughout the United States interviewing gay and lesbian folks about their lives. He's particularly interested in relatively levels of "outness" in rural, suburban, and urban areas, as well as different geographical regions -- are queer folks living in Minnesota more or less likely to be out than those living in Missouri? Alabama? Massachusetts? What are their connections to both the queer community and their local community? Do they live openly with a partner, or go away to the big city once a month to party at the gay bar or women's center? If they attend church, are they open about their sexuality and if so how did the congregation react? Aware that "gay America" is often imagined as existing solely in urban locales, Miller purposefully sought out interviewees in more rural locations, as well as talking with people in such iconic queer spaces as San Francisco.

His portraits are memorable and contain a healthy diversity -- though I doubt his sample would stand up to any sort of statistical analysis. We meet gay dairy farmers, lesbian homesteaders, a lesbian minister put on trial for her relationship with another minister's ex-wife, and a gay mayor of a small town in Missouri, and even such high-profile queer folk as Armistead Maupin and Susie Bright. For obvious reasons, I enjoyed the chapter on sex-positive lesbians and the porn wars, in which Miller adopts the bemused tone of an outsider trying to understand the complex dynamics of a turbulent family reunion. While he falls into some unfortunate stereotypes of 1970s lesbian identity (i.e. that until the 80s most lesbians were content not to have much sex), his account does highlight the way in which gay male and lesbian subcultures were so divergent at that point (in the mid-80s) that Miller himself struggled to find mutual points of reference.

His portraits are memorable and contain a healthy diversity -- though I doubt his sample would stand up to any sort of statistical analysis. We meet gay dairy farmers, lesbian homesteaders, a lesbian minister put on trial for her relationship with another minister's ex-wife, and a gay mayor of a small town in Missouri, and even such high-profile queer folk as Armistead Maupin and Susie Bright. For obvious reasons, I enjoyed the chapter on sex-positive lesbians and the porn wars, in which Miller adopts the bemused tone of an outsider trying to understand the complex dynamics of a turbulent family reunion. While he falls into some unfortunate stereotypes of 1970s lesbian identity (i.e. that until the 80s most lesbians were content not to have much sex), his account does highlight the way in which gay male and lesbian subcultures were so divergent at that point (in the mid-80s) that Miller himself struggled to find mutual points of reference.Art and Sex is Picano's anecdotal history of the Gay Presses of New York, beginning with his own SeaHorse Press (1977) and moving through the consolidation of GPNY (1981) into the late 1980s. It's a rambling narrative, mixing highly amusing -- and often pointed -- snapshots of his interactions with various authors, artists, and other members of the gay literary scene in with a more chronological assembly of factual details. The overarching narrative is one charting the movement of queer literature from the margins to the (slightly more) mainstream: from a time when you had to know the bookstore from which to special order titles, to a time when major publishing houses were seeking to re-issue gay classics. One of my favorite anecdotes involved a bookseller of the old guard who refused to stock a GPNY title because he deemed it not gay enough. This same bookseller was also extremely lax about his accounts, and when Picano called him up about the outstanding balance essentially told Picano he should be grateful the bookstore was willing to stock his titles at all. While Picano doesn't explicitly make the connection between this interaction and the mainstreaming of queer culture (at least in New York) post-Stonewall, it is clear that there has been a generational shift in expectations between when the bookstore owner set up shop and Picano began publishing -- no longer were publishers of "gay" literature held hostage in quite the same way to the whims of distributors.

Picano also, inevitably, touches on the way AIDS ravaged his circle of friends and acquaintances during the 80s, and to a lesser extent writes about the tension between gay (male) presses and the underground lesbian presses, particularly as they connected to the broader subculture of lesbian-feminist separatism. He writes with frustration about the double-bind he experienced when literary events he organized would be accused of lacking female representation -- but the women he asked to participate would refuse on principle because the event was not organized by their own people.

All in all, I'd say Miller's book is of more general interest than Picano's, but that both will be of use to anyone with either a casual or scholarly interest in first-person narratives of queer subcultures in twentieth-century America.

*I'm using "gay and lesbian" quite deliberately because for the most part both authors are dealing specifically with gay and lesbian-identified people, not a more polyglot group of queer folks. Their framework is rooted very much in the political identities of the 70s-90s, not the increasingly fluid understandings of sexuality that have seeped into our twenty-first century identities (Jack Harkness would be proud!).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)